We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“Before the year is out.”

John O’Brien, from the poem Said Hanrahan

Australian’s have a distinct way of speaking. Like other nations, our accent is becoming more generic, but it still has a distinctive flat tone.

Back in the mid-1960s, Alistair Ardoch Morrison, writing as Affabeck Lauder (get it*) took our accent to extremes and wrote two books about it, the first of which was Let Stalk Strine.

How much is it became emma chisit, decimal currency became dismal Guernsey, and Sydney became Sinny.

If you want to convey an Australian in your book you wouldn’t write it filled with the over-the-top accents from something like Let’s Stalk Strine. You’d normally try to find a word or two to convey the accent.

One such word used to be ‘mate’. Memo to all you people out there who use it. Yes, some Australians do say, “Mate.” More than most of us realise, in fact, but it’s actually a heavy word, and if you use it more than once or twice it comes across as a parody.

So an occasional, “Look, mate,” might convey an Australian—or equally, someone from the UK—but sprinkle ‘mates’ liberally throughout the book and your Australian is nothing more than a caricature.

Heavy-handedness kills believability dead. When writing characters with accents, or with distinct ways of speaking, we’re often told to go softly on the accent, use one or two words to emphasise. A single word usually suffices. “Rooned”, for Irish Hanrahan, for example, in the John O’Brien poem, Said Hanrahan, works.

The trick is to make that word sound natural. ‘Gonna’ is a word commonly used to do this. Or ‘gunna’ if you’re trying to do it with an Australian accent. I’ve read stories where the author tries to make it sound as if their character is poor and uneducated. They change every ‘going to’ to ‘gonna’ (or ‘gunna’). It doesn’t work because every other word around it is in the author’s voice, and for many writers that’s an educated voice.

The ‘gonna’ jars, because an educated person does not normally contract their ‘going to’s’. Of course, in real life. people do. The vice principal at my old secondary school used to say ‘gunna’. But he spoke well. I bet when he wrote it down, however, he wrote ‘going to’.

And speaking of poorer people, why do so many people try to write them as stupid? (I’ve read a lot of that lately too.) They’re not. People across every socio-economic status have a range of intelligence. Some of them are stupid, some of them are smart.

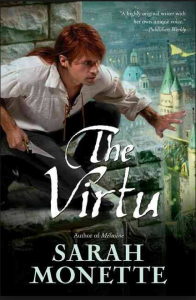

Actually, if you want to see how someone presents a truly smart person who comes from a disadvantaged background (and sounds like it), try Mildmay from Sarah Monette’s Doctrine of the Labyrinths series. I love Mildmay, he’s one of my favourite characters ever, and he’s a truly smart man.

“You don’t got to come if you don’t want.”

…

The lock was gorgeous, the work of Selenfer and Kidmarsh, who’d been the hot boys in locks back in the Protectorate of Helen. I ain’t much of a cracksman, not for the fancy stuff, but I could handle an old S-and-K combo. I was glad there was nobody standing behind me with their pocket watch, the way Keeper used to, but it wasn’t no trouble.

Melusine, Sarah Monette

Now that’s how you do it.

*Alphabetical order

And Let Stalk Strine translates to ‘Let’s Talk Australian’.